Cremation is now so familiar that we take it for granted, but it only became legal in Britain thanks to a man who, at the age of 84, was nearly lynched for trying to burn the body of his infant son. It’s an extraordinary story, but that word applies to almost everything about the life of Doctor William Price of Llantrisant.

The fifth of seven children, William was born near Caerphilly on the 4th of March 1800. His father was an Oxford graduate and an ordained priest in the Church of England, but he never practised: by the age of thirty he had been declared a lunatic and as he was regarded as a danger to himself and others, he spent most of the rest of his life tied to his armchair. Many of his children also suffered from mental illness of one kind or another, and William himself was not spared. As his great-grandson the art critic Andrew Gibbon-Williams told me, these days Price would probably be diagnosed at schizophrenic or at the very least bi-polar, but he was a very bright boy indeed.

Although the family lived in poverty and William spoke only Welsh until the age of ten, he flourished at school where he set his sights upon a career in medicine. He apprenticed to a surgeon in Caerphilly before studying at the London Hospital in Whitechapel where he excelled, becoming the youngest ever member of the Royal College of Surgeons at the age of 21. On graduating he returned to Wales to be appointed surgeon for two of the biggest industrial concerns in the country, the Tinplate Works in Treforest, and the Chainworks at Newbridge which supplied chains and anchors to the great Victorian engineer, Isambard Kingdom Brunel.

Price was a well-respected doctor. He was a pioneer of social health care, instituting a system whereby workers could pay him when they were well so he could treat them for free when they were sick, but even then, he courted controversy. He denounced his fellow practitioners as ‘poison peddlers’ who profited from the sick instead of curing the illness and he was eccentric by the standards of the day in his championing of natural medicines, vegetarianism, women’s rights and free love: over the years, he fathered a considerable number of illegitimate children, all of them female.

By the middle of the 19th century Wales was developing a sense of itself as a nation not least through the bardic poetry of Iolo Morganwg. Price was one of Iolo’s most devoted disciples: together they reinvented the druidic cult, campaigning to build a Museum of Wales and establishing the very first National Eisteddfod.

As Price became increasingly outspoken, his political views became evermore radical and that brought him to the attention of The Chartists who made him their leader in Pontypridd. Price was very much involved in the planning for what was intended to be a national uprising and he spent months gathering support, using ‘Welsh language lessons’ as a cover for military training in the surrounding valleys.

The uprising was to begin in Newport on the morning of Monday 4th of November 1839. Ten thousand Chartists had assembled outside the town the previous evening but after a night of pouring rain, only half that number remained to confront the muskets of the 43rd Regiment of Foot outside the Westgate Hotel. It was an unequal contest which lasted only twenty minutes and left only twenty people dead, but the battle of Newport became famous as ‘the last armed rebellion on British soil’ and it caused panic at Westminster. The leaders were convicted of treason and condemned to be hung, drawn and quartered before common sense prevailed and their sentences were commuted to transportation for life.

Sought by the police, Price sought sanctuary in Paris and while there, he claimed to have had ‘an epiphany’. Browsing one day in the Musée du Louvre he saw an inscription on a piece of ancient Greek pottery and realised that only he as a druid could understand what it meant. Inspired by his discovery, he wrote a book in which he prophesied that his first-born son would be a new Messiah who would sweep Christianity away and re-establish Britain’s pagan identity.

When Price returned to Wales the following year, he began to dress as a druid. He wore his hair over his shoulders and made a crown from the body of a fox. He continued his work as a doctor, and he continued to campaign on cultural issues and raise money for philanthropic purposes, but he became increasingly notorious as ‘a vexatious litigant’. Price enjoyed nothing more than throwing a courtroom into confusion by calling his infant daughter as his ‘learned counsel’ or by refusing to swear on the bible because the maps of Judea were incorrect and despite – or perhaps because of this – he often won.

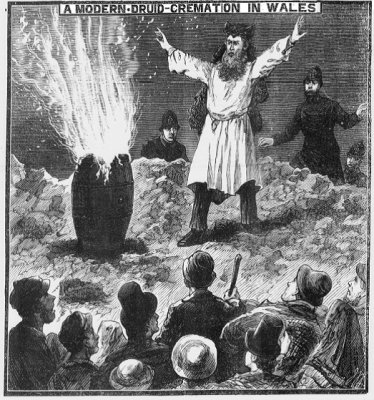

At the age of 71, he left his job at the Tinworks and opened a new surgery in the medieval hilltop town of Llantrisant and it was there, on his 83rd birthday that he married a woman almost sixty years his junior, Gwenllian Llewellyn, in a pagan ceremony that he conducted himself. The following year, he achieved his dream of fathering a druidic messiah. He named his son Iesu Grist, (Jesus Christ) but before he was five months old, the boy suffered a convulsion and died in his father’s arms. Four days later, Price wrapped the infant’s body in a blanket, picked up a flask of paraffin and walked to the top of the hill that overlooks the town, East Caerlan.

It was a cold, dark Sunday evening, and as the people of the town left their evening services they must have looked up and seen the flames against the night sky. Several hundred were prompted to investigate and when they realised what Price was doing, they flew into a rage; it was all the local police could do to prevent them from lynching him there and then.

Price was put on trial in Cardiff, where he faced two charges. Firstly, that he had cremated the baby before an inquest could be held into its death, and secondly, that he had caused a public nuisance by holding an open-air cremation. The case drew hundreds of spectators to the assizes, generating massive attention and widespread press coverage. The then aspiring author Arthur Conan Doyle wrote a serialised account for one of the weekend papers and Price, who defended himself, revelled in the attention. As he said of burial in court, “It is not right that a carcass should be allowed to rot and decompose in this way. It results in a wastage of good land, pollution of the earth, water and air, and is a constant danger to all living things.”

These arguments might seem eminently reasonable today but they were radical then and Price was lucky in the bench’s choice of magistrate. Not only had Justice James Fitzjames Stephen spent time in India where he had witnessed a traditional Hindu cremation, but he was also a supporter of the Cremation Society of Great Britain which had been founded just nine years earlier, in 1874.

The trial was the breakthrough the society had been waiting for. Justice Stephen ruled that William Price had committed no crime, the body of Iesu Grist was returned to him, and in March 1884, in front of a small but respectful crowd, it was once again committed to the flames on top of East Caerlan. Ever the showman, Price had minted 3,000 bronze coins to commemorate the event and sold them at threepence each.

Cremation was not illegal, but in the eyes of the public it was still far from decent and it took another eighteen years before Parliament passed the first Act ‘for the regulation of burning of human remains’ in 1902. By then Price himself was long dead, but he died confident that his own cremation would go ahead exactly as he’d planned it.

Nine tonnes of coal were delivered to the summit of East Caerlan where two walls and an iron grid had been built to hold the custom-made coffin. As Price had insisted, Gwenllian sold tickets for the event and no fewer than 20,000 people attended. The atmosphere was more like a carnival than a funeral and by midday, every one of the town’s 27 pubs had run dry. Price was carried from his home and although his family were not allowed a druidic ritual, for the very first time in a Christian funeral ceremony, the Bishop of Llandaff agreed to include the words ‘I commit this body to fire.’

No matter how ‘modern, clean and scientific’ cremation might claim to be, it was far from an instant success. Mrs Jeannette Pickersgill became the first client of Britain’s first commercial crematorium in Woking on the 26th of March 1885, but she was one of only three cremations that year. There were ten in 1886, but for the next fifty years cremation’s appeal was strictly limited to the intelligentsia. Famous names on the roll call of Golders Green, London’s first crematorium, include those of the psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud, the artist Charles Rennie Mackintosh and the sexologist Havelock Ellis, but it wasn’t until the Archbishop of Canterbury was cremated in 1944 that the Anglican Communion embraced the process and cremation began to become more socially acceptable.

The hundredth crematorium opened in Salford in 1957, the two hundredth in Worthing nine years later. When Pope Paul VI finally allowed Catholic priests to conduct cremation services in 1963, the trickle became a flood. It took only five years before cremation overtook burial as the preferred choice in England and Wales. It took a further nine years before the same thing happened in Scotland, but it wasn’t until 1996 that the first crematorium opened its doors in Northern Ireland.

There is no area of life where change happens more gradually than in death and just as it took more than a century for cremation to go from unthinkable to unremarkable, it will take time for most of us to begin to consider the other options that are beginning to emerge around the end of life.

In August 2019, Washington became the first state in the USA to allow ‘natural organic reduction’, an eco-friendly process whereby a human body can be reduced to a cubic yard of compost in less than two months. ‘Natural Organic Reduction’ as it’s currently known, provokes the same sense of unease and discomfort in most people today that cremation did in the mid 19th century, but in a world threatened by climate change, it offers the possibility of a less damaging way to leave this world. Not ‘ashes to ashes’ but ‘soil to soil’.

[…] of Common Prayer to write a series of essays. ‘Earth to Earth’ is about natural burial; ‘Ashes to Ashes’ tells the almost unbelievable story of how cremation became legal in the UK, ‘Dust to […]

Absolutely fascinating story Tim and reinforces my fear of the burny fire! I’ll be thinking about this all day!

Thank you so much, Jane! I really appreciate you taking the time to read this.

[…] Ashes to ashes, indeed. […]

I appreciate your interest in my ancestor – the only really interesting one I have. My paternal grandmother referred to him as ‘uncle’, but she could never have met him. To call him eccentric even by the standards of his time is an understatement. He was a radical. Any anti-Establishment point of view he would grasp. He mastered PR before it had been invented. Dressing up and all that. I reckon his post-Chartist spell in Paris was a fantasy. I really doubt whether he even spoke Welsh, which he professed to be able to do. His relics, such as they are, are housed in St Fagan’s Folk Museum outside Cardiff. All pretty threadbare. Actually, he was, more or less, a ‘hippie’ avant la lettre. But, to his credit, he did establish our rights of Cremation. Point was, that hardly anyone had thought about its legal basis previously, so he was pushing against and open door. It had never been ‘illegal’; it was just that no one had ever thought of doing it. Oddly, there is a very fine statue of him in Llantrissant.

Thanks for finding this, Andrew – it’s a fascinating story that would make a good TV drama.