As we begin to wake up to the damage we’ve already done to our planet and belatedly try to mitigate it, we should say a silent ‘thank you’ to the first people to recognise our duty to protect the natural world: the Zoroastrians.

The world’s first monotheistic religion, and the inspiration for Judaism, Christianity and Islam, Zoroastrianism is probably the oldest religion in the world. It’s definitely the least well-known, even though a Google search for ‘famous Zoroastrians’ will take you straight to an article about Freddie Mercury, the late lead singer of Queen. It’s now accepted that the Three Wise Men who followed a star to the stable in Bethlehem were not kings but Zoroastrian priests. The ancient Persian word for priests is ‘Magi’ and that is the root of ‘magic’ which is apt, because once again we are coming to realise that science and magic are often the same thing.

Zoroastrianism takes its name from its prophet, Zarathustra, who lived in Persia almost 4,000 years ago and it was the dominant religion in the area until the arrival of Islam following the Arab conquest of the 7th century. Many Zoroastrians promptly fled to Gujarat in western India, where they became known as Parsis after their Persian origins. They brought with them a distinctive set of beliefs and practices; their mantra of ‘good thoughts, good words and good deeds’, their temples lit by sacred flames that can never go out, their style of cooking, currently being made famous by Dishoom, and their scientific understanding of the consequences of death and decomposition. Zarathustra decreed that nature was sacred, and as burial polluted earth and water and cremation polluted fire and air his followers had to devise another way of returning to the elements. They came up with an ingenious one; they deliberately and ritually laid out the bodies of their dead to be eaten by vultures.

With their bright yellow eyes, bald heads and scaly reptilian necks, vultures are not the most attractive of birds but as their scientific name attests, the Cathartidae are the cleaners and purifiers of the natural world. Feeding almost exclusively on dead and decaying animals, vultures protect us from potential disease and a wake of vultures (yes, that really is the collective noun) can completely strip a carcase of flesh within an hour. Some, like the Lammergeier, eat the bones too and we should be grateful to them because throughout human history, animal carcases have been one of the main vectors of disease, from the rats that spread bubonic plague to the bats who brought us Covid-19.

When the Zoroastrians first arrived in India fifteen hundred years ago, they must have been delighted to find more species of vultures than they’d left back home, and even today, there are nine in India compared to six in Iran. After their fire temples, the first structures the Zoroastrians built in their adopted country were simple platforms for the dead but these soon grew into substantial, castle like structures called dakhma. On their roofs, bodies were laid out in a series of concentric circles: men on the outside, women in the middle and children at the centre. After the vultures had done their work, any bones that were left would be left to dry in the sun before being collected and stored in an ossuary. To the Parsis, there was nothing macabre about giving their bodies to the birds; on the contrary, they regarded it as their last act of earthly generosity.

The first person to write about the Zoroastrians’ distinctive funeral rites was the Greek historian Herodotus in the 5th century BC but it wasn’t until the 19th century that an English colonial administrator coined the evocative term, ‘the Towers of Silence’. Most are long since abandoned but some survive to this day. Two of the best-preserved are on hilltops outside the Silk Road city of Yazd in the middle of the central Iranian desert, but others are still in use and easier to visit. The Parsis of Mumbai continue to bring their dead to their Towers of Silence in the middle of the city where their white-robed priests continue to intone prayers in the long dead language of Avestan, but the mourners no longer look to the skies for the descending flocks of purifying birds. Just like their Hindus neighbours, Parsis now have to be cremated, because the vultures upon which they were able to rely for almost 6,000 years have almost completely disappeared.

We are very aware these days of the diseases that cross the boundary between humans and animal species, but we are less conscious of those that travel in the opposite direction with equally devastating effects. In the 1960’s the Swiss company Ciba-Geigy synthesised a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug called Diclofenac to treat human diseases like gout. In the 1990’s farmers in India and Africa began using it on cattle to rid them of fever and lameness, but it wasn’t until this century that scientists began to realise that it had already caused a catastrophic collapse in the vulture population.

Even in small doses, Diclofenac is toxic to vultures because it causes a form of gout that leads to kidney failure. Within a decade, India’s vulture population had declined by 95% and the White-rumped Vulture, the Indian Vulture, the Red-headed Vulture and the Slender-billed Vulture are now on the World Wildlife Fund’s Critically Endangered List. The governments of India, Pakistan, and Nepal banned the drug in 2006, making its use an imprisonable offence two years later, but it was too late for the vultures; Birdlife International says that their extinction remains a very real possibility and an article in The Economist in August 2023 shows how that proved fatal for humans too, causing the mortality rate to rise significantly in districts where vultures had previously been common.

It was too late for the Parsis too. They weren’t the only people to practice ‘excarnation’ as it is technically known; the Plains Indians of North America did it too, and even today there are a few people in the more remote parts of Sikkim, Mustang, Bhutan and Tibet who have the skills to prepare a body for ‘bya gtor’ or sky burial, but thanks to Diclofenac, there are fewer vultures there now too, so that way of returning to nature has almost gone. Despite that, the idea of returning to the elements remains a powerful one, and surprisingly the place where it has become a reality is in the most death-denying culture of all; the United States of America.

I bequeath myself to the dirt to grow from the grass I love,

If you want me again look for me under your bootsoles.

It was in the spring of 2013 that an architectural student at the University of Massachusetts Amherst submitted her Master’s Thesis entitled “Of Dirt and Decomposition: Proposing a Place for the Urban Dead”. Taking a quotation from Walt Whitman’s poem ‘Song of Myself’ as its starting point, Katrina Spade’s thesis challenged conventional funeral practice by proposing a meaningful and ecologically beneficial alternative. Spade’s vision was to create a building in the centre of New York where the city’s dead could decompose together and where, at the end of the process, their loved ones could take them away in the form of compost. She called it, ‘Soil to Soil’.

Tall, boyishly slim and charismatic, Spade grew up in a medical family where it was fairly normal to talk about death and dying at the dinner table, and she was still in her early teens when she began giving serious thought to the question of what would happen to her body after she died. As an American, she was already very conscious of the culture of death denial in which she lived.

As she says, “Today, almost fifty per cent of Americans choose conventional burial, which begins with embalming, where morticians drain bodily fluids and replace them with a mixture designed to preserve the corpse and give it a lifelike glow. Then the body is buried in a casket, in a concrete lined grave. All told, in American cemeteries, we bury enough metal to build a Golden Gate Bridge, enough wood to build 1800 single family homes and enough embalming fluid to fill eight Olympic-sized swimming pools.”

All over the world, cemeteries are reaching capacity, but cremation isn’t the sustainable answer that we once thought. It destroys the potential we have to give back to the earth after we’ve died. It uses an energy-intensive process to turn bodies into ash, polluting the air and contributing to climate change. According to Spade, “cremations in the US emit a total of six hundred million pounds of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere every year. The truly awful truth is that the very last thing that most of us will do on this earth is poison it. It’s like we’ve created, accepted and death denied our way into a status quo that puts as much distance between ourselves and nature as is humanly possible.”

“Our modern funeral processes are meant to stave off the natural processes that happen to a body after death; in other words, they’re meant to prevent us from decomposing, but the truth is that nature is really, really good at death. When organic material dies in nature, microbes and bacteria break it down into nutrient rich soil, completing the life cycle. In nature, death creates life.”

Spade began to think about redesigning the whole funeral process from scratch, using nature as a guide. It was while she was mulling over that idea as an architecture student that her phone rang; it was her friend Kate, who said, “hey! Have you heard about the farmers who are composting whole cows? And I was like, hmmm…”

It turned out that farmers had been practising something called ‘livestock mortality composting’ for decades. “In the most basic set up, a cow is covered in a few feet of woodchips, and left outside for the breeze to provide oxygen and rain to provide moisture. In about nine months, all that remains is a nutrient rich compost. The flesh has been decomposed entirely, as have the bones.”

Spade describes herself as ‘ a decomposition nerd’. But as she said, “I am far from a scientist. And one way you can tell this is true is that I have often called the process of composting magic. All we humans need to do is create the right environment for nature to do its job. Instead of fighting them, we should welcome microbes and bacteria in with open arms. These tiny amazing creatures break down molecules into smaller molecules and atoms which are then incorporated into new molecules. In other words, that cow is transformed. It’s no longer a cow, it’s been cycled back to nature. See: magic!”

One dream, one soul

One prize, one goal

One golden glance of what should be

It’s a kind of magic

from “A Kind of Magic”, by Queen

The lightbulb went off and Spade began designing a system that would take these principles and transform human beings into soil. That was the thesis for her Master’s degree which she developed into ‘the Urban Death Project’ which launched in autumn 2014 and to my eyes, looked very much like a contemporary Tower of Silence. As the journalist Brendan Kiley reported in 2015,

“The Urban Death Project is still in the design stages, but its outlines are becoming clear. The centerpiece of the idea is an approximately three-story-high building in an urban center where people could bring their dead. Friends and family would accompany the departed up a circular ramp to the top of the “core,” or central decomposition chamber. They could then perform a “laying-in” ceremony, during which the body would be set into a mix of wood chips, straw, and other organic material. The core would be divided into approximately 10 “bays”—almost like elevator shafts—with several bodies in various stages of decomposition in each bay, separated from the bodies above and below by several feet of wood chips. Gravity and microbial activity would regulate the speed of each body’s descent, and, after a few weeks or months (this part is still in the research stages), loved ones would be able to return to the building to pick up the remains, which have become humus. Spade alternately describes this process as “cremation by carbon.”

Most importantly, no single body would undergo the process alone. Every body would have company on its way down. This is the Urban Death Project’s most radical proposition, the thing that sets it apart from cremation or burial: It deposes the idea of individuation in death. No human body, of course, decomposes on its own. People’s ashes mix in a cremation retort, and caskets in cemeteries decay together. But our current death-care rituals allow us to pretend otherwise. An urn of ashes represents a person. A burial plot represents a person. Compost is collective.”

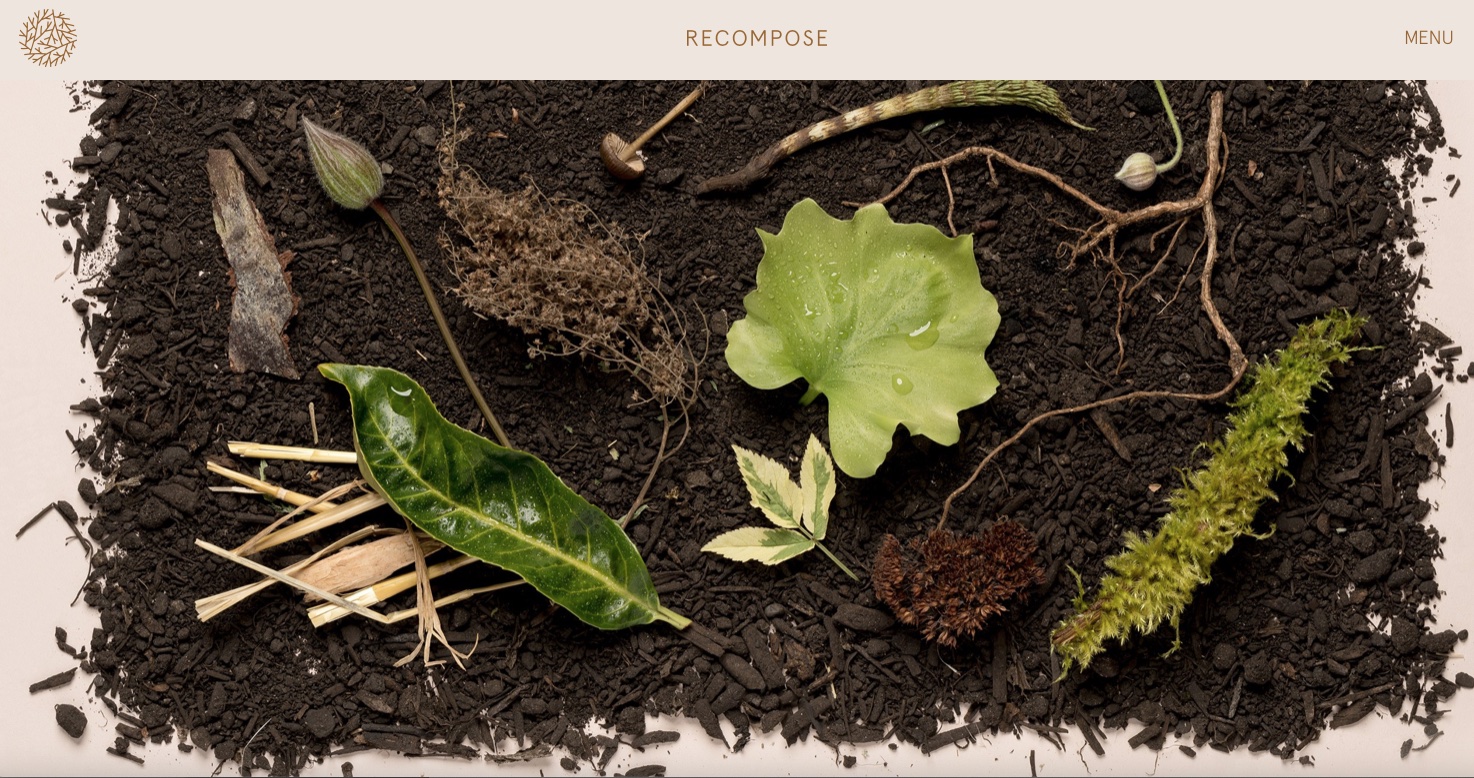

Less than two years later, Spade gave a TEDx talk called “When I die, Recompose Me” which struck a chord and the idea reached a whole new audience when it was shared on Twitter by Margaret Atwood, the author of A Handmaid’s Tale. Atwood herself became an investor during the autumn of 2017 by which time The Urban Death Project had become Recompose, and the idea of communal decomposition had been quietly dropped. Bodies would instead be laid into individual vessels, a shrewd judgement that Spade and her team made as they pursued their goal of making ‘natural organic reduction’ law and one they achieved astonishingly quickly when in May 2019, Governor Jay Inslee signed Proposition SB5001 into law, making Washington the first state in the world to allow “the contained accelerated conversion of human remains to soil”.

Seven years after Katrina Spade submitted her Master’s Thesis, Recompose finally opened its doors in December 2020. She had originally planned to set up in Seattle’s SoDo district, an edgy former industrial area not unlike New York’s more famous SoHo, but COVID forced the company to scale back its ambitions and set up a smaller operation twenty minutes out of town. As Brendan Kiley writes,

“Outside, the entrance to Recompose looks like most of its neighbors — just another unit in a tall, almost block-sized building with plain metal siding and big, roll-up warehouse doors. But inside, it feels like an environmentalist’s version of a sleek, futuristic spaceship: spare, calm, utilitarian, with silvery ductwork above, a few soil-working tools (shovels, rakes, pitchforks) on racks, bags of tightly packaged straw neatly stacked on shelves, fern-green walls, potted plants of various sizes.

One immense object dominates the space, looking like an enormous fragment of white honeycomb. These are Recompose’s 10 “vessels,” each a hexagon enclosing a steel cylinder full of soil. One day in mid-January, eight decedents were already inside eight vessels, undergoing the process of natural organic reduction (NOR) or, more colloquially, human composting.”

The demand for what Recompose offers is clearly there. In February 2021, (when I wrote this) the company had to temporarily close to new admissions because they were at capacity and Spade and her six-strong team are hard at work constructing vessels and planning another location with space for 50 more by the end of that year. As Spade says, “that’s the point of all this: science and magic are kind of the same thing; we are on a journey to transform this incredible human event.”

Anna Swenson, the company’s communications manager, talked me through the process. Each body is laid onto a three cubic metre pile of woodchip, alfalfa and straw in a stainless-steel vessel, where it remains for 30 days. For the first 72 hours, the vessel is heated to 131º Fahrenheit to break down pathogens like faecal coliform and salmonella and over the next 30 days, air is blown through it to oxygenate the compost; temperature readings are taken every ten minutes and the vessel is slowly rotated several times. At the end of the process, Recompose and an independent third party test the resulting soil for heavy metals, like mercury from amalgam dental fillings and to check that all the pathogens have been duly broken down.

The compost is then transferred to a ‘curing bin’ for a few more weeks to settle and release more CO2 before the process is complete and the rich humus is finally ready to be collected by the donor’s family. They can then either donate the soil to an ecological restoration project on the nearby Bell’s Mountain, take away the full cubic yard or take a 64-ounce box and donate the rest to the mountain. So far, most of Recompose’s clients have chosen option three but serendipitously, their first two clients were both organic farmers, so their families took the soil home to replenish the land that was once theirs.

‘The tipping point’ is that moment in the evolution of an idea when it seizes the collective consciousness and ‘goes viral’. In a 1996 article in the New Yorker it was Malcolm Gladwell who borrowed the term from epidemiology and applied it to human behaviour, noting that ‘sometimes the most modest of changes can bring about enormous effects’. He remembered an old ditty of his father’s – ‘Tomato sauce in a bottle. Nothing comes and then a lot’ll.’

It’s too early to say if Katrina Spade’s idea is the breakthrough moment we’ve been waiting for, but the early signs are promising. In Washington State, two more ‘natural organic reduction’ facilities have already opened since the law changed in 2019. Return Home of Aubern have coined the term ‘Terramation’ and their fees are a few hundred dollars less than Recompose. The non-profit Herland Forest Natural Burial Cemetery charges even less, but Spade is sanguine. “I believe we desperately need change in the way we care for bodies, physically and emotionally,” she said. “So there should be a lot of people out there doing this. Do I have to love them all? No. But it’s not surprising to see competitors finally arrive.”

It took thousands of years before humanity replaced ‘earth to earth’ with ‘ashes to ashes’. I can only hope we don’t take as long to embrace ‘soil to soil’ but as Katrina Spade says, “The death care revolution has begun; it’s an exciting time to be alive!”

I originally wrote this piece in early 2021 but what prompted me to share it now was the news that in January 2023, Organic Reduction has finally been approved right where Katrina Spade always wanted it to be, in the State of New York. I am delighted for her, and I can only hope that some day soon, some equally public spirited entrepreneuse will pick up her baton on this side of the Atlantic. For me, that day can’t come too soon.

[…] In August 2019, Washington became the first state in the USA to allow ‘natural organic reduction’, an eco-friendly process whereby a human body can be reduced to a cubic yard of compost in less than two months. ‘Natural Organic Reduction’ as it’s currently known, provokes the same sense of unease and discomfort in most people today that cremation did in the mid 19th century, but in a world threatened by climate change, it offers the possibility of a less damaging way to leave this world. Not ‘ashes to ashes’ but ‘soil to soil’. […]

[…] in the UK, ‘Dust to Dust’ is about what actually happens when a body is cremated, and ‘Soil to Soil’ is about vultures, Freddie Mercury and the unlikely marriage of science and […]

[…] This – I hope – could be one of them. […]