It’s eight years since I first went to Binning Wood. I’d been asked to conduct a ceremony there for Julia, a wife and mother who’d been diagnosed with pancreatic cancer just three months before her death at the age of just 49. A bubbly force of nature, Julia loved fast cars, had an outfit for every occasion and worked in London as a surveyor until she was diagnosed with ME. When her marriage ended not long afterwards, she decided that the best way to recuperate would be to help her aunt Sheena to run her cattery two miles past the middle of nowhere in West Fife and it was there, over a hot litter tray, that she met the man who was to become her husband, Cameron.

There was plenty to say about Julia’s life and a lot of people who wanted to say it, so given that it was early winter and the first flakes of snow were already dusting the nearby Lammermuir hills, we decided to do her ceremony back to front; the pall bearers would carry her woven willow casket from the hearse, the family would lower it into her final resting place, I would say a few words, and then we’d all jump back into our cars and head off to her warm and welcoming local pub where we could take all the time we needed to celebrate her life.

I remember walking up the long, unmade road through the forest to meet the funeral director, Chris Harkess. The trees rose a hundred feet above me on either side of the track and what light there was had that steely brightness that often presages a fall of snow. The cortege hadn’t arrived so I had time to take my bearings and the first thing I noticed was that Julia’s grave was nowhere to be seen. In conventional graveyards, you can always spot the three-sided wooden box where the gravediggers pile up the earth, but there was no soil box here, and no gravestones either. The forest floor looked entirely undisturbed; all I could see were trees and leaf litter. “This is weird,” I said. “Where’s the graveyard?” Chris just smiled. “It’s all around you. Look again.”

Binning Memorial Wood is a wood within a wood. Part of a three-hundred-acre forest of Scots pine, Douglas fir, larch and oak, its six acres of beech trees were planted shortly after the end of the Second World War. Tall, straight and shallow-rooted, beech groves have been associated with ritual throughout human history and the vaulting arches of Gothic cathedrals consciously echo their shape. If oak is the king of the forest, beech is the queen and its golden-green canopy is so dense that few plants can grow beneath it. Instead the ground is covered in its distinctive three-sided seed pods, or ‘mast’. If we were in Spain, farmers would bring their pigs to feed on it, but that tradition died out in these islands centuries ago, which is why the Spanish have their highly prized pata negra ham and we don’t. The reason a beech grove makes such a good burial ground is that the tree’s root system is almost as vertical as its trunk; if you walk three steps in any direction away from the base you’re standing on soil, and that is where Binning Wood’s inhabitants are to be found.

The first thing I noticed was an oval mound of earth rising slightly above the leaf litter that surrounded it. The second was a loosely tied bouquet of red roses still in perfect bloom. A few yards further on, peeking out from under yet more leaves was a pale, heart-shaped stone. There was no name inscribed on it, just the message, “Mum. In our hearts you’ll always stay”. As my eyes adjusted to the low light and the lie of the land, I began to notice more mounds here and there amongst the trees; the new ones were much higher and lighter in colour while the oldest had subsided over time to become an almost invisible dark stain upon the earth.

Some had no memorials of any kind, while set into the flat faces of modestly-sized boulders, others had plates of polished stone inscribed with names and dates, poems, messages and epigrams. Mick’s ‘words were kindness, his deeds were love’. Marion was ‘Warm, witty, wonderful’; Dylan, who died at less than a year old, was ‘a brave boy who showed us beauty, courage and love beyond our imagination’.

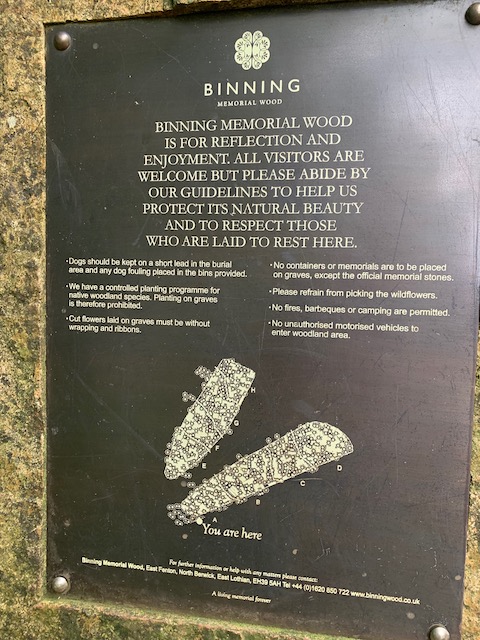

These days we rarely commit a body to the ground. In the UK more than three quarters of us choose cremation, and even in the USA where burial is still more popular, coffins are not laid directly to earth, but into a underground concrete vault. The rationale for that is that when the coffin and its contents decompose, the vault prevents the ground from sinking so the lawn stays level, and the grass is easier to mow… Binning Wood’s ethos is exactly the opposite but like any exclusive community, it has its rules. Your coffin can be made of any kind of wood, from oak and pine to willow or cardboard, but it must be fully bio-degradable and entirely free of plastic or metal. Any flowers planted on your grave must be native and wild, and most importantly of all your body must not be embalmed, because Binning Wood’s aim is to return you to the elements.

Natural burial may be rare, but it is not a new idea. Judaism and Islam have followed essentially similar practices for thousands of years, but now that environmental awareness is on the rise, it is an idea whose time has come again. The graves at Binning Wood are no more than four feet deep; their two-foot covering of soil makes the smell of decomposition undetectable to humans and animals and because the unembalmed corpse is in a biodegradable coffin, its nutrients can be quickly reabsorbed into the ecosystem by organisms in the soil.

It was in the 1970’s that the astrophysicist Carl Sagan became famous through his book and TV series ‘Cosmos’ and it was he, not Joni Mitchell, who first told us that we are stardust. “The cosmos is within us. The nitrogen in our DNA, the calcium in our teeth, the iron in our blood, the carbon in our apple pies were made in the interiors of collapsing stars. We are made of star-stuff. We are a way for the universe to know itself.”

A few years ago in his first series on BBC, professor Brian Cox said more or less the same. “Our story is the story of the universe. Every piece of everything, of everything you love and everything you hate, of the thing you hold most precious, was assembled by the forces of nature in the first few minutes of the life of the universe, transformed in the hearts of the stars or created in their fiery deaths. And when you die, those pieces will be returned to the universe in the endless cycle of death and rebirth. What a wonderful thing it is to be part of that universe. What a story, what a majestic story.”

In the gentle silence of the wood, it was Brian Cox’s words that I spoke before we laid Julia to earth and after the words of committal, I also said the familiar phrase from the Book of Common Prayer: ‘earth to earth, ashes to ashes, dust to dust’. Science and religion are often opposing ways to understand the world, but I find it comforting that science has finally confirmed what for centuries was only a poetic truth; life really does come from death, although not as reincarnation or eternal life, as we had previously imagined. “For now we see through a glass, darkly”, as Saint Paul wrote in one of his famous letters to the community of early Christians that he founded in Corinth: we still do.

It’s only recently that science has confirmed something else we have always intuitively known; trees are vitally important to the health of the world. Connected underground by a mycorrhizal network that allows them to communicate with one another, trees create the air that we breathe and their lives are infinitely longer than our own. The Japanese weren’t the first to realise that shinrin-yoku, orforest bathing was good for the mind and soul, but cognitive psychology now confirms that spending time in nature improves our sense of wellbeing. As Carol Ann Duffy puts it in her poem,

The forest

keeps a different time;

slow hours as long as your life,

so you feel human.

There are now more than three hundred woodland burial sites in the UK. Most start out as green fields but Binning Wood is unusual because it has been there for centuries. It was named after its original owner, John Binning, the first Earl of Haddington who planted it sometime in the early 17th century when he bought the estate of Tyninghame for “two hundred merks”, about a hundred and thirty old Scots pounds. In 2002 when his descendent the eleventh Earl put the estate back on the market, two local farming families, the Grays and the Dales, competed to buy up most of the prime arable land. Neither of them really wanted the wood, but John Gray bought it anyway, setting up a forestry operation to generate a modest revenue from timber products. His son Ben and his wife Sarah came into the business a few years later, and began looking into different ways to use it. They wanted to do something that wouldn’t take away from the feeling of the place so initially they thought about a gallop or a cycle track, but it wasn’t until Ben was visiting a cousin down in Essex where he came across a woodland burial site that he thought, ‘this might be interesting’.

He expected to have to deal with a whole lot of red tape so he was delighted to discover when he spoke to East Lothian Council that you don’t need a licence to bury a human body. When he came home and told Sarah, a former quantity surveyor, she said, ‘I don’t believe that for one minute’, but it turned out to be true. They did need to get permission from the council, and they did have to liaise with the Environmental Protection Agency who dug some holes to check their water sources. They also needed to consider issues like road access and parking but all in all, the planning went through pretty quickly. As Sarah told me, they got a lot of help and advice from Rosie Inman Cook, who runs the Association of Natural Burial Grounds and an educational charity called the Natural Death Centre.

In her fashionable Barbour jacket, stylish Dubarry boots and colourful silk scarf, countrywoman Sarah Gray would look entirely at home at a point-to-point. She makes an unlikely sexton, but when she’s not involved in the many other aspects of running the family farm, that is what she is; the sexton, or caretaker of Binning Wood. We spoke in her office amongst the trees, a Hansel and Gretel cottage where she meets families to talk about their plans, and while she freely admits she never for a moment imagined herself in this role she also says she’s pleasantly surprised to have found her niche.

“I’ve always loved helping people,” she said, “and although our meetings with families are sometimes clouded in sadness, I get a lot of satisfaction from helping them with this part of dealing with their loss. It’s wonderful to know that by creating the wood, we’ve done something that brings so much comfort. There’s no time limit on ceremonies here. There’s no pressure to move on because there’s another family waiting to come in after you and people just love the wood and its atmosphere. It’s not a sad place at all; there’s something very calm and peaceful about it and I think that’s why people love it so much.”

Binning Memorial Wood opened without fanfare in May 2010 and Sarah and Ben welcomed their first resident, a local teacher, later that year. They soon learned that woodland burial brings with it a unique set of challenges, the first of which was recording exactly where their residents are. They tried digital mapping, but that didn’t work; they tried using a drone, but that didn’t either, so they ended up mapping the grove the old-fashioned way, by hand, on paper, with a tape measure. They then counted all the trees and numbered them, so that a grave could be marked as being 3.72 metres from this tree, 4.62 from that one and 5.48 from a third. The good news for the Grays is that there is now an app which makes things a bit easier. The developers of What3words have divided the entire world up into blocks 3 metres square, and any given one of those blocks can be identified using just three words, a system which the company claims is every bit as accurate as GPS. If you have the app, you can try it for yourself. Just enter “speedily.tricks.stuff” and you should find yourself virtually transported to the gate that bars the entrance to Binning Memorial Wood.

There are many other ways in which the Grays depart from contemporary burial practice. Because the graves are so shallow they don’t need the six-foot deep shoring that is required to make conventional graves safe, although they do still lay wooden boards on either side to avoid any risk of collapse and ensure that the weight of the coffin and its bearers is evenly distributed. After the ceremony they put the excavated soil back into the grave; the excess forms a mound which has then to be stepped on, stamped down upon and compacted. They actively welcome the participation of families who want to do that themselves, or even to dig a few spadefuls at the start of the process. Couples who want to remain united in death can be buried side by side, rather than one on top of the other, knowing that they will stay like that forever, or at least for as long as the planet survives.

“Since we started doing this,” said Sarah, “my attitude to death has changed absolutely. Like most people, death wasn’t something we ever spoke about in our family, but now it’s a subject Ben and I can discuss without getting upset. When I’m dead, I know I’ll be in here somewhere; obviously it’s the cheap option for Ben! But seriously, one of the reasons we did this was to protect and preserve the forest, and when we learned that the use of the land could never be changed if people were buried here, we immediately knew that this was the right thing to do.”

Filmmaker Ruth Barrie’s son Saul is part of Binning Wood now. He had been diagnosed with a brain tumour at the age of four and although the doctors got rid of the cancer, he developed a condition called posterior fossa syndrome and lost all movement and speech. He lived with terrible pain for a further four years before he died at home and Ruth and her husband William brought him to the wood where Sarah and Ben gave them a plot free of charge. As Ruth told Vicky Allan in her book, “For the Love of Trees”, “Sol stayed in the house for about ten days following his death. It was good to have that time – very powerful and necessary, I think. I couldn’t imagine him suddenly being gone.”

We had a burial at Binning Wood. It was lovely to do that for Sol. I felt happy about the way it went. He was in a natural wicker basket. The feeling in the woods was sacred, so beautiful. Sol was lowered into the ground and there was a celebrant who had some special words to say and we all threw in the traditional rosemary and lavender and rose petals. A friend arrived at my shoulder and said that she would like to chant a song. It was a beautiful moment.”

“Then there was a little moment of silence, and just wind, rustling through the trees. In that moment, I felt like I could sense the forest move and live and breathe. I felt reassured that I was not leaving him somewhere cold and awful.”

“The couple who run Binning Wood asked if we would help with the tucking in, the putting the earth back in, and friends and family took turns. I do love the idea of him going back to the earth. The first time I went back to the woods following the funeral, it felt like I could go there all day, and just be writing, or drawing and writing, being there. You sit there and once the waves of emotion pass through you, you can look up and the beeches are waving above you and birds flit through the branches and you feel the forest as a living, breathing entity. I love that Sol is part of that now.”

If you go down to the wood today, you’re not in for a big surprise; Binning looks pretty much as it did when I first went there. If you’re lucky, you might see a sparrowhawk, or hear a greater-spotted woodpecker. At the right time of year, you might find snowdrops or even chanterelles, but although there are now a few dens made from branches and couple of reclaimed timber benches, there are still no rain-soaked teddy bears or supermarket flowers wrapped in cellophane. We humans find it hard to leave only footprints but if you really do want to return to the universe and get yourself “back to the garden”, then natural burial is the way to go.

You can find out more about natural burial at The Natural Death Centre website, which has a list of all the natural burial grounds in the UK, along with many other resources, including advice on organising a funeral without professional help.

[…] I was inspired by that passage from the Book of Common Prayer to write a series of essays. ‘Earth to Earth’ is about natural burial; ‘Ashes to Ashes’ tells the almost unbelievable story of how […]