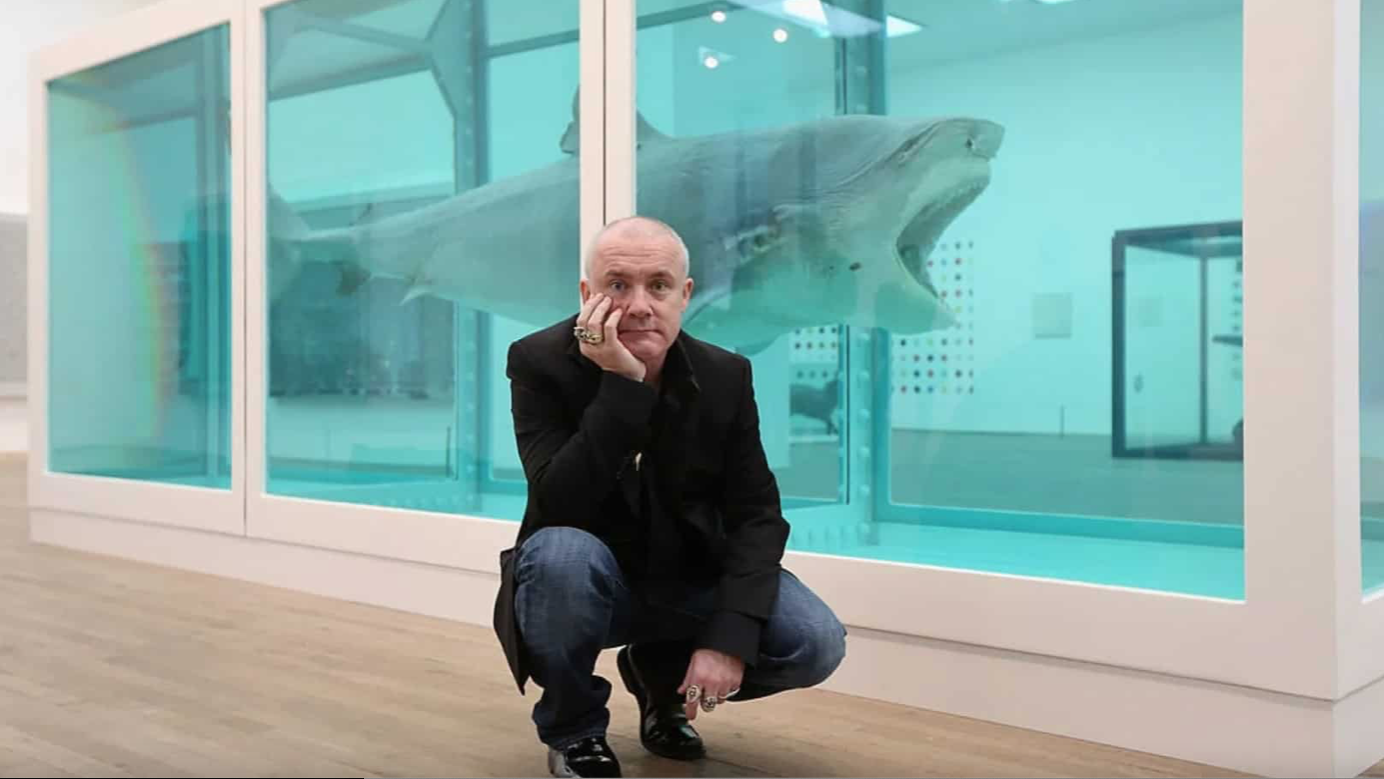

It was in 1991 that Damian Hirst burst into the public consciousness with his sculpture of a 14-foot tiger shark entitled The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living.

As a teenager, he’d visited the Anatomy School at Leeds University to draw dead bodies that had been preserved in formaldehyde. They made him feel sick at first, but he soon became fascinated by the subject that has made him one of the world’s most successful living artists.

Big, scary and relentless, the shark is a simple but potent metaphor for death. The strange thing is that while we can’t get enough of death in art, literature and drama, we refuse to contemplate our own. The title Hirst chose for his sculpture sums up the bind in which we’re caught: we are simultaneously fascinated by death and repelled by it. We instinctively know we don’t want to think about it, but until very recently we had no idea why.

People have been thinking about how our brains work since Aristotle, but it’s only comparatively recently that neuroscience has been able to show us how the actions of neurons and molecules in our brain relate to the way we behave and in November 2019, I began to see stories in the press about a team of Israeli researchers who claimed to have discovered how our brains prevent us thinking about our own death.

I spoke to the lead author, Doctor Yair Dor-Ziderman, at the Safra Brain Research Center at the University of Haifa. A slim, bespectacled dark-haired father of four young children, Yair has an unusual back story.

On leaving school he was called up for mandatory military service in the Israeli Defence Forces and during that time, his childhood friend Arik Frankenthal was abducted and killed by Hamas.

At Arik’s funeral, as everyone around him was collapsing in grief, Yair was so numb he couldn’t cry and afterwards, he began to wonder why. That question prompted him to become a neuroscientist and to spend the next ten years of his life studying how we deal with death.

As he told me, “the brain is a prediction system which makes judgements about the future based on patterns learned in the past. It has statistical probabilities about what the world is like, and it doesn’t wait for information to arrive before it decides what to do.”

“We do it all the time. If I put something into your hand that looks very light but is actually very heavy, you’d be surprised when your hand dropped whereas if you had already known it was heavy, you’d have been prepared. This predictive ability is something we don’t think about. It’s like when we’re walking, we’re constantly preparing and adjusting our footsteps to the terrain without thinking.”

Every close-up magician knows the brain is easy to trick. If you show someone three cards with apples then slip in a pear, they’ll be surprised because they’re expecting another apple: their brain has learned the pattern. It was this prediction system that Yair and his team wanted to measure in relation to death.

They ran two experiments which were carried out under scientifically rigorous conditions. “Twenty-four healthy participants (11 female, mean age 26.4 years, SD 1⁄4 4.8) were recruited for experiment 1” as the article in Neuroimage soberly records. “All participants were right-handed, fluent Hebrew speakers, with normal or corrected vision and with no self-reported history of neurological or psychiatric disorders.”

Before taking part, the volunteers were photographed against a white wall; they were asked to wear a neutral expression as their picture was taken and their photographs were subsequently cropped to exclude their hair, ears and neck.

They were tasked to watch a screen while their brain activity was monitored and in the first experiment, they were shown a number of repeated images in succession; their own face, (‘self’) the face of another person, (‘other’) and a third face that was a 50/50 mixture of both (‘self/other’).

At the same time, words appeared in random order; a third of them were neutral, a third were negative words, and the other third were words that related to death, like “funeral”, “grave”, or “burial”.

They included negative words, Yair explained, to clearly show that their findings related to death, not just negativity, because the team’s intuition was that our brains are willing to associate negativity with self, but not with death.

The volunteers were told to press a button whenever they saw a face wearing sunglasses, but what the experiment was really measuring was their subconscious response to the combination of words and faces.

In the first experiment, the volunteers’ brains responded the same way to all the images where the words were neutral, whether the photograph was their own, (‘self’), that of a stranger (‘other’) or of a deviant (‘self-other’).

They gave a “surprised” response to the images of strangers or deviants next to a word that related to death. But when the volunteer saw their own face (‘self’) next to a word associated with death, their brain did something completely unexpected.

It didn’t show surprise at all. Instead, it shut down its prediction system.

“Why did it do that?” I asked.

“The brain is very sensitive to deviant stimuli” Yair replied. “If we hear a sound and then we hear a different one, the brain immediately registers a quality of surprise. It has a model of the world, and it is continually updating it. In our experiment, what we saw was that the brain responded to all the faces in the same way. The only thing that was different was its response to this word in the background, so what is important – and what the study shows – is that when ‘death’ and ‘self’ appear together, the whole death-denial mechanism is down-regulated. The fact that the presence of this word completely annihilated this very basic perceptual brain process was really surprising. I expected an effect, but I expected it be smaller – not that it would be completely annihilated!”

“The brain has a kind of shield which insulates it from thoughts of death,” Yair continued. “That doesn’t mean it can’t feel the fear of death which is one of its most important functions and which has been with us ever since our brains evolved when we were vulnerable hunter gatherers out on the savannah. But these experiments weren’t about that primal fear of death, and our volunteers didn’t experience fear. Although they saw lots of negative words and words related to death, at a conscious level, they just shrugged them off but subconsciously, the brain noticed them. At some level, the brain always knows. It is always monitoring and doing something in order not to associate the idea of death with self and in the second experiment, I was trying to show how it does that.”

This time, the volunteers watched a six-second video clip, during which one face slowly morphed into another. Again, the face might be their own or that of a stranger, but it was always the face of someone of the same gender, and the volunteer’s task was to press the spacebar on their computer at the precise moment they felt that the morphed face no longer represented its original identity. As in the first experiment, before the clip ran, a word appeared at the top of the screen and stayed there for the duration of the video.

“What the results show”, said Yair, “is that when we are uncertain of the identity of the person we are seeing, it takes a longer time to identify the change. The brain takes a longer time to do the emotional processing because it is trying to protect itself from the idea of death by projecting it onto others.”

Doctor Dor-Ziderman’s experiments raise lots of questions, not least about the nature of thought. If our brains won’t let us think about death, then who’s doing the thinking?

Perhaps our inability to think about our own death isn’t wilful blindness after all. It may even be a positive selection by evolution, a lucky side effect without which we would find life impossible, a conclusion with which Yair agrees – but only up to a point.

“There is a case for that theory, but you have to look at it in context. You have to go back once again to when we were vulnerable hunter gatherers out on the savannah, when people were dying all the time, killed by animals, disease or warfare. In those circumstances, you would need a death denial mechanism just to be able to function, but if you’re a young person today, you only meet death in movies and video games. You don’t get the experience in life at all; you don’t get the smell and the touch of someone that you know, like your father or grandfather, actually dying by your side. I don’t have the evidence – yet – but I don’t think the fear of death is hard-wired. I think it’s cultural. We live in a death-phobic culture.”

“On our bedside table, we have a picture of my wife’s late father, and our children ask us, ‘who is he?’ So my wife explains, ‘He’s my father’, and the kids say, ‘where is he?’ My wife says, ‘he’s dead’ and they ask, ‘why is your daddy dead?’ so they start thinking about death and trying to relate it to themselves and from that very moment, they’re picking up on your reaction.”

“They’re not picking up on what you are saying, but your embodied presence. If you are tense, they see that, and that’s what they learn because their bodies’ physiology resonates with ours. The death-denial mechanism exists, but in today’s world it’s completely out of balance and the way the medical profession talks about death contributes to that too.”

“Doctors see themselves as fighting death so if you die, it means that ‘you lose’. That’s kind of how death is conceived in the Western World and as you approach the end of life, you will be encouraged to do anything to delay it, even for a short time. It’s a very deeply engrained attitude, which is why, when a terminal patient is offered experimental treatment, even with long odds of success and terrible side effects, they will tend to say ‘yes’, and their family will say ‘yes’, because ‘yes’ means ‘more life’.”

“The only moment you are allowed to die is when you say ‘OK I’m suffering so much I can’t do it anymore’. The death denial mechanism is very powerful, and if we don’t check it, it gets out of hand – at least that’s what I think is happening.”

Just as death has been professionalised and medicalised, it has also been secularised in a way that I am only now coming to realise feeds into our fear of death.

Religions have had centuries to devise rituals that give form to grief, and which offer comfort to the bereaved; in our newly secular world, we are only just beginning to develop a set of practices to replace them. The content is not fixed, and the grammar is unfamiliar, but the aim is the same; to alleviate anxiety and to facilitate acceptance.

Yair talked about the Tibetan Buddhist tradition, in which there is a practice called The Nine Cemetery Contemplations.

Apprentice monks were required to spend time in a ‘charnel ground’ and practise a form of meditation called “navasīvathika”, during which they would relate to the process of human decomposition.

The first stage was to spent time with recently dead bodies as they began to bloat, discolour and ooze. The second, a week later, was to be present to the stench released by the corpse as it was torn apart and eaten by birds and animals; I could go on, but I’m sure you get the picture…

As Yair said, “The monks were being trained to do this with full presence of mind to gain insight to this horrible experience but they already had the spiritual framework of compassion which allowed them to cope with it.”

“We are currently running an experiment to find out if meditation can have a positive effect on our death denial mechanism, and the early signs are encouraging, but actually, I don’t think it’s very complicated. As Marcus Aurelius said, facing your own death puts you in alignment with the nature of things. It keeps you very clear about what is important and it reminds you that you have a very limited time to achieve it, so don’t waste it.”

There is comfort in knowing that it’s not our fault that we cannot bring ourselves to think about our own death, but not even Doctor Dor-Ziderman’s explanation makes it easy to address the matter in hand. Thinking about our own death takes an extraordinary act of will, and courage of a kind that we don’t see in the movies.

Other than meditating or following the example of Marcus Aurelius, I asked Yair if he knew of any other ways to help us think the unthinkable.

“Yes”, he replied. “There is a whole branch of psychology you can explore called ‘existential psychology’ which aims to make us more conscious and more accepting.”

As the name suggests, existential psychology has its roots in the writings of the 20th century French philosopher Jean Paul Sartre who coined the phrase, ‘man is condemned to be free’. As he saw it, in a world without gods, the human task is to create our own purpose and meaning. Taking responsibility for our own existence is anguishing, he argues, but it is only by doing so that we can fulfil the potential of our lives. ‘We are our choices’, Sartre famously said, and what we become in life is up to us.

(By the way, if that sounds like humanism, that’s not surprising. It comes a 1946 essay called “Existentialism is a Humanism”.) One of Jean-Paul’s less well-known quotations is this one; ‘life begins on the other side of despair’.

Admitting that death is frightening is the first step; the next is to talk about it.

Excellent as always Tim

Thank you Jane: that means a lot to me.

Thanks Tim, what an interesting and thought provoking piece.

I’m very thankful not to be an apprentice monk!