As a child, Fiona Christison really wanted to study medicine but it didn’t work out. Instead of going to university as she’d hoped, she fell in love, married an accountant and became the mother to two children. By the time they had left school, her marriage had ended, and she had become a landscape gardener, a job she felt was her vocation.

A quiet retiring woman who didn’t enjoy mixing with people, Fiona led a simple life and enjoyed walking in the countryside and climbing hills. Two years before her death in 2018 she was diagnosed with lung cancer, which came as a surprise because she wasn’t a smoker, but she accepted the diagnosis with equanimity because she had already made plans for her death. There would be no funeral. Instead she would finally go to university where her body would be used to train a new generation of doctors.

Richard Gillanders was Fiona’s partner for more than forty years. He told me that she was interested in the life of the mind, and that mineralogy and archaeology were just two of the interests they had in common. He also told me that long before they met, Fiona had already signed the forms to ensure that her body would be given to the School of Anatomy at the University of Edinburgh and that she had made that decision partly because she wasn’t religious, but mostly because medicine was a tradition of long standing in her family.

Fiona’s great-grandfather Sir Robert Christison had been what the Americans call ‘a big man on campus.’ Born at the end of the 18th century, Christison had been Professor of Medicine at the University of Edinburgh for fifty years. He had gone on to become Physician in Ordinary to the Queen in Scotland and President of the British Medical Association, but his reputation was first made when, as an expert at the trial of the body snatchers Burke and Hare, his hostile forensic interview had destroyed the reputation of their client, the distinguished and popular anatomist, Doctor Robert Knox.

Knox was not on trial and he was exonerated by the subsequent enquiry but Christison’s assessment that Knox was “deficient in principle and heart” ensured his reputation never recovered. On one occasion, a howling mob hung Knox’s effigy from a tree outside his house on Arniston Square, and set it alight, but the former military doctor was not intimidated. He continued to teach anatomy in the city for several years before moving to London where he died of a stroke and was buried in an unmarked grave in Brookwood Cemetery. It took more than a hundred years before it was rediscovered by his successor as Conservator of the Museum of the Royal College of Surgeons, Professor Eric Mekie, who commissioned a modest memorial to acknowledge that Knox’s reputation had been unfairly defamed.

Fiona’s ancestor was very much a man of his time. Not only had Christison done his best to ensure Knox’s downfall, he had also adamantly opposed the idea that women should be allowed to study medicine so it’s ironic that Fiona was one of his few descendants who didn’t enter the profession. Her grandfather and great-uncle had been distinguished physicians, her father had studied medicine and her son, his wife and their two children had all become doctors in their turn, so giving her body to the school of anatomy was Fiona’s way of contributing to the ever-growing body of medical knowledge and human understanding.

“When Fiona told me she was giving her body to medical science, it didn’t bother me at all,” said Richard. “I was comfortable with that right to the very end. I don’t think that what happens to your body after your death makes a lot of difference. To be honest, I don’t fancy either of the alternatives; cremation or burial. What’s important is being able to remember the person who has died.”

“Fiona was adamant that she wanted to die at home. The district nurses and the palliative care team were excellent and they made every provision so that her wishes could be fulfilled. Strangely, given her family history, she had an aversion to hospitals and doctors, and when she became ill the last thing she wanted me to do was to contact her son but eventually she became so ill that he had to be told and I am glad, because had it not been for the support I got from his family and his sister, I would have been in a terrible state when she died.”

“Being doctors, her son and daughter in law knew exactly how long Fiona had to live so they suggested I take a break. I think they knew she had only a day or two to live and they looked after her while I went up to Nethybridge in the Highlands where Fiona had a house and where we used to go walking with the dogs. Sure enough, it was while I was there that she died and again, I have to admit I was quite happy about that because I’m not sure how I would have coped had I been with Fiona at the time.”

When Fiona died, her body didn’t go – as most of ours do – to a funeral parlour. Instead it was taken to the back door of the Old Medical School which still stands on Teviot Place, just half a mile uphill from where Burke and Hare plied their murderous trade in the seething tenements of the Grassmarket.

Some years ago when the BBC discovered that I too had opted to donate my body, I was given a tour. I saw the skeleton of William Burke that still hangs in its glass case in a dusty corner of that august Victorian building, and I was taken down its broad sandstone staircase and led through a succession of locked doors to the receiving room where, under a pale blue sheet on a stainless-steel table, lay the body that I was to meet. The producers of the Religion & Ethics show on BBC Radio Scotland wanted to see how I would cope with being confronted with the consequences of my decision, but if they were hoping for drama they were disappointed.

Nobody pulled back the sheet to reveal a disfigured corpse. All I saw was a cross-section of someone’s forearm, laid bare by a scalpel to reveal the complex tangle of veins, arteries and flesh that lie below the skin. In the formaldehyde infused air of the teaching room, the exposed antebrachium with its median nerve and its flexor carpi radialis looked more like an expensively detailed theatrical prop than anything human, but as Professor Gillingwater later told me, you can’t get better than the real thing, which is why bodies – and body donation – are still so important in the teaching of anatomy.

These days, a civilian like me is no longer allowed to make that journey. Bio-security is one concern but a more pressing one is the advent of social media. To prevent the possibility that someone might take inappropriate photographs, all mobile phones are banned and only verified students and staff are admitted to the teaching rooms.

Iain Campbell is the Anatomy Manager at the College of Medicine, and one of his jobs is to prepare donated bodies for their last journey. Placed into plain white cardboard coffins first thing in the morning, they leave the department in batches and travel in an unmarked van to Mortonhall Crematorium where they are unloaded and brought directly to the cremators via the back door. There are no mourners, and there is no ceremony: in a very real sense, the last rites for these generous souls have already been performed and their deaths have been gratefully honoured by the young doctors who have learned from their final gift.

Not everyone wants a funeral. When David Bowie died, he left strict instructions that his body was to be anonymously cremated with no one in attendance and during the Coronavirus pandemic, the number of direct cremations soared. If only a few people can attend the funeral, went the logic, why don’t we just wait and have a memorial ceremony without the body when we can all get together again? In a sense, funerals are not for the dead, they’re for the living and I believe that the only people who should make that call are the bereaved themselves: Richard certainly thought so.

“One of the best things about the body donation programme was that we managed to avoid having a funeral. Let’s be honest: funerals can be depressing. Some funerals I’ve been to have been really good, but they can be far from uplifting. I don’t think Fiona liked the idea of having a funeral and I don’t either. All these people turn up who you’ve never seen before: they just appear out of the woodwork and I don’t know… The great thing about giving your body to science is that you just fade away… In Fiona’s case there was no notice in the newspaper; it was just left to the family to communicate as they felt fit, and I think that’s great.”

Fading away into non-existence doesn’t mean being forgotten though. For generations, having a grave to tend and visit provided a focus for grief and memory, but as fewer and fewer of us choose that route out of life, it’s becoming much less of an issue.

As Richard said, “It doesn’t bother me that we don’t have a grave to visit or ashes to scatter: it doesn’t affect me at all, although the family felt that it would be nice to have some sort of memorial to Fiona, and her daughter suggested a seat. We often visited the coastal village of Earlsferry in Fife and when we got there, we’d sit and have our picnic on one of the memorial benches there on Chapel Green so that was what we did.

We got a bench made and we put a simple plaque on it, and if you go there now and stand at the foot of Chapel Point, you can see Fiona’s bench up there, looking out over the bay, but I don’t need to go there to think about her. I think about her most of the time already, and although I’m on my own now, I still do all the things we used to do together.

We used to climb Arthur’s Seat and Blackford Hill and I still do that now. I can’t go over to Earlsferry now because of lockdown but when it’s over, I’ll go back there again, but wherever I am, and whatever I’m doing, I’m remember Fiona most of the time.”

A convinced non-believer, Richard was surprised how much he enjoyed the memorial that the Medical School holds in May every year at Greyfriars Kirk. “I really enjoyed the ceremony. Some of the students attended as well as the staff and they had all the photographs of the donors at the front of the church so it was very, very uplifting and the speeches were very good. I was very touched that the professor of anatomy referred to the people who donated their bodies to medical science as ‘the silent teachers’: it really was excellent. I’m not religious and nor was Fiona but it was very uplifting to be able to share the service with so many relatives of other people who’d donated their bodies. It wasn’t depressing at all, and I thought it was great!”

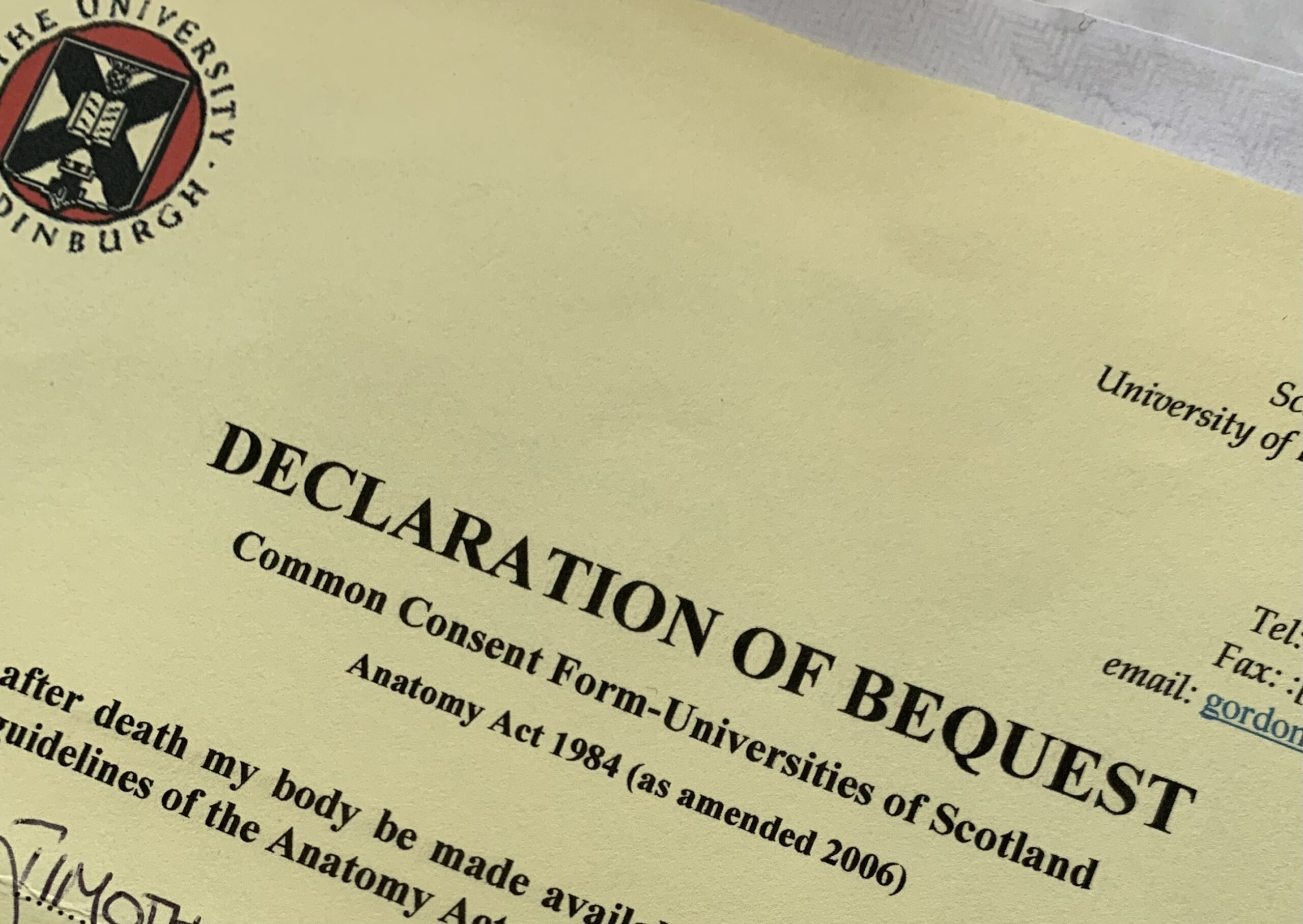

Like Fiona, Richard has also decided that when the time comes, he wants to become one of the silent teachers. “I’m 72 now and I’m still alive and well for the moment, but I already have all the paperwork: I just need to complete it and send it to the University!”

0 Comments Leave a comment