It’s odd that we use this phrase so often, but never take it at face value.

“Funerals are for the living” as one of my mentors told me when I was training, and that is true, but it doesn’t mean that all we can talk about during the ceremony are the memories of the living. The dead can speak too – if they take the trouble to write down their thoughts during the course of their life, and that is what exactly what William McGinnis did.

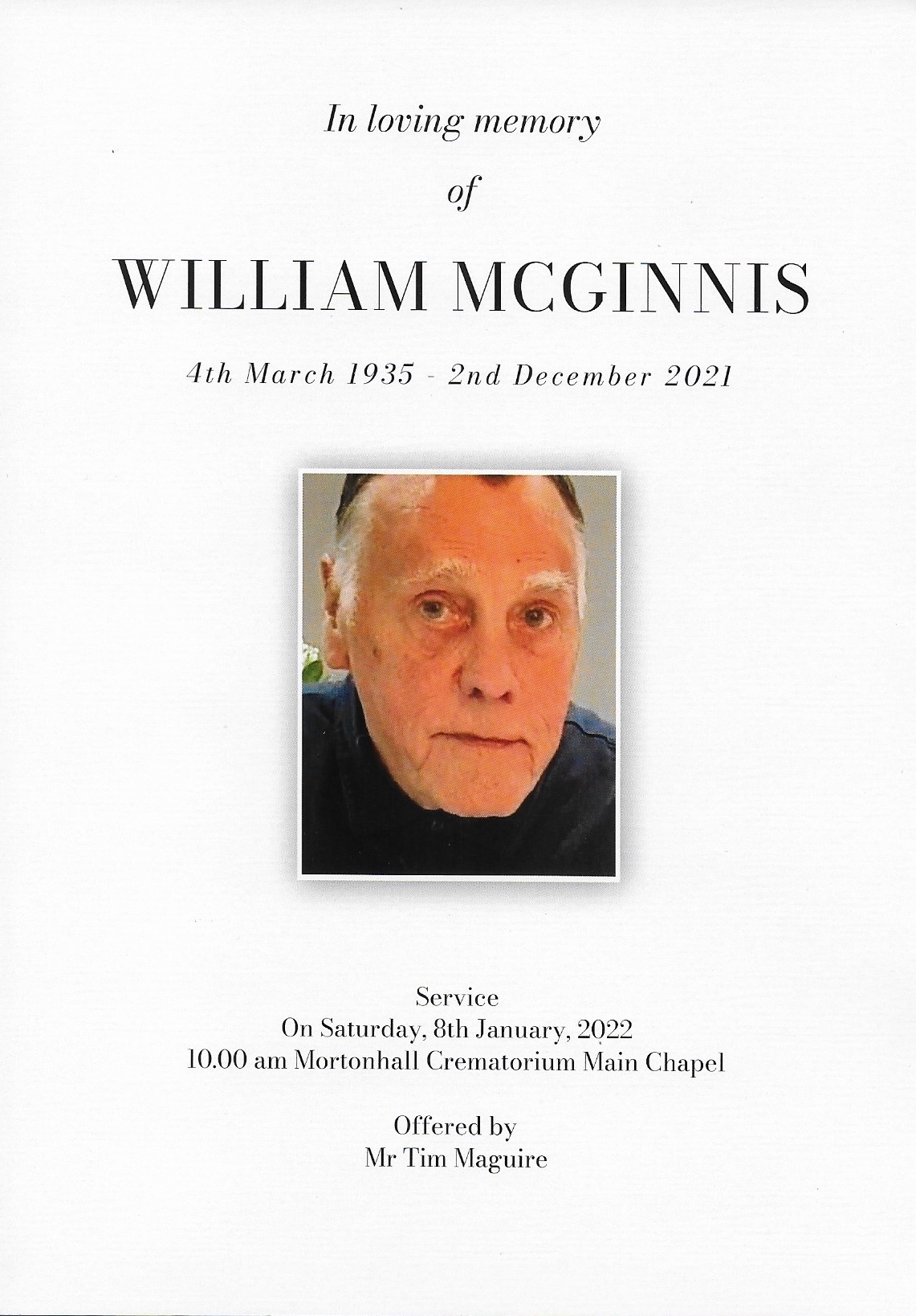

Wullie, as he was known to his friends, had an extraordinary life and when he was 83 years old – three years before he died – he took the time to write about it, to leave a memoir for his family. When they sent it to me, I realised it was something more than just a memoir; it was a time capsule from an almost forgotten era.

The generation who grew up in the 1920’s and 30’s are almost gone and the world in which they lived has vanished with them. In some ways, that’s a good thing.

Wullie was seven years old before his life changed in a way that nobody could now imagine. As he wrote,

“One day in spring 1942, the person who I believed was our mother took us on a bus journey to a place called Rutherglen and then to a convent called Belleview which was run by the Sisters of Charity, and left us there. About a fortnight later our father came to see us, but he left us there too. We were there for 8 years.”

Wullie’s wee brother Davie joined him not long afterwards; that was when Wullie discovered the meaning of responsibility.

“I quickly discovered that not only was I responsible for my own behaviour, but also Davie’s. If he broke the rules, it was me who was taken to task. I had to learn how to darn socks and I had to darn Davie’s socks too.“

He also discovered the wages of sin…

“So began our indoctrination. I was informed that I had a soul which was pure shining white and that each time I committed a sin, a black mark was made on it. There were two types of sins, mortal and venial. Mortal sin was heavy duty and made big black marks on the soul. Venial were minor. If you died with a mortal sin on your soul, it was straight to the burning fire. Venial got your purgatory. I really believed this for a good few years and tried to be a good catholic.”

Life in Belleview was hard.

“Certain rituals had to be followed on a daily routine. Each morning Miss Mary would clump down the wooden stairs, enter each room and clap her hands, at which we would all sit up and say morning prayer. We dressed, then congregated in the communal room where we said another prayer. We then formed in pairs and marched over to the conservatory for breakfast. The portions were small with little variety. It was at breakfast that the so-called “pee the beds” were made to stand in the middle of the conservatory with their wet sheets around their necks. Then we were marched back to our quarters.”

At the age of fifteen, Wullie’s dad came to take him away to live with him, his new wife and his new son. Wullie had to earn his keep, which he did by working at the old Dumfriesshire Dairies.

“I had to get up at 4am and get to Fountainbridge to meet the milk cart. I earned 5 shillings a week, but my father took a half crown for food and lodging plus a shilling for socks, (this has always mystified me as I was a very good darner). Although he was strict, I was happy to have more freedom and a shilling and sixpence to spend on comics, sweets, and crisps.”

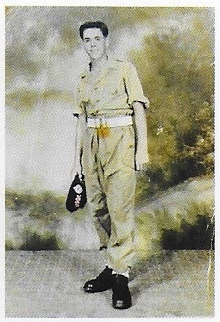

At the age of 18, he and his pal Jimmie joined the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, and were sent to Stirling Castle for training where everything had to be done at the double. After a boring spell of guard duties at Redford Barracks, Wullie and Jimmie were posted to British Guiana in South America.

As he wrote, “Everybody was excited. In September 1953, we boarded an aircraft carrier called H.M.S. Implacable and billeted in one of the massive aircraft hangers, tying our camp beds to thick ropes, in case of rough seas. It was here I acquired my taste for rum. The journey took four weeks and as we sailed into warmer climates we sunbathed on deck. We disembarked in Trinidad where we boarded another ship that took us to Georgetown, the capital of British Guiana, where we had to perform guard duties for Government House in full kilt order. In our off-duty time, Jimmie and I explored the town, discovering the bars and houses of ill repute. I did not attend the latter as I had reservations about females and mortal sin from my indoctrination at my catholic orphanage days.”

“After six months our company was relieved and we were sent to a new camp at a place called Atkinson Field. This was like a holiday camp compared to Georgetown. Our duties were always finished by twelve noon because of the heat and we were free to wander or sunbathe; there was even a swimming pool. At night there was a NAAFI bar, where spirits were a penny-halfpenny a nip and beer was tuppence a bottle, but nobody drank it. Cola was free.”

“Alas all good things come to an end and we were posted to Germany where things were much stricter. We had more weapon training and I became quite proficient with the Bren gun. I could strip it blindfolded. One of our duties was at Spandau prison in Berlin where prominent Nazis like Rudolf Hess, Himmler, and Admiral Donitz were being held. The guard posts were mounted on the walls and fitted with search lights. Each sentry had a rifle and a spell of duty was eight hours. Most of the prisoners were no bother except for Hess, who would stand under a sentry post and shout and rave in German which nobody understood.”

When he was demobbed, Wullie came back to Edinburgh where he lodged with Ma Begbie in Stenhouse Avenue West. “She only had one leg and used a homemade crutch, but she made great mince and tatties, she smoked, and took a wee nip and she played a mean game of brag, so we got on well.”

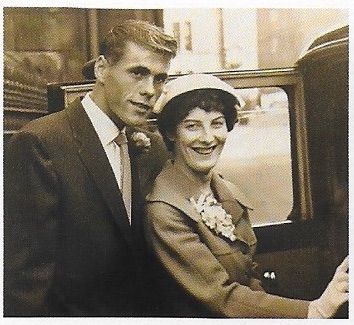

It was here that he met the woman who was to become his wife.

“A guy from my milk run days called Johnny Beattie was winching a lass who worked at a factory in Fountainbridge. The Factory made sutures for the NHS and they were having an open day where Johnnie had an invite for himself and a friend. I agreed to go and on the day of the visit, I met Alice’s pal, Margaret Low. I was not initially impressed because she was wearing a white coverall with a cover on her head and heavy black glasses. Not long after this Johnny asked me if I would like to go to a party for Alice’s brother’s 21st and I agreed to go. That night I saw Peg again, and what a difference – she was dolled up to the nines. She wore a figure-hugging blue striped dress and no glasses. Well, my flabber was duly ghasted.”

“Eventually I eventually managed to get a date. We had agreed to meet outside the Regal picture house in Lothian Road. I watched her get off the bus, cross the road, then walk right past me. That’s when I realised why she wore glasses!”

I could tell you lots more about Wullie’s life, but I hope you get the picture – and my point. One of the problems of living to a grand old age is that your friends often die before you do, and the stories that they remember go with them.

If you’re lucky, your children may remember some of the tales you told them, but that’s not always the case. That’s particularly true for mothers of that generation, who were so busy bringing up a family in an age before automation let alone home delivery, that they didn’t have the time to talk about themselves even if they wished to.

As Rutger Hauer’s character in the movie Bladerunner says, “all these memories will be lost in time, like tears in rain.”

What I especially loved about Wullie’s ceremony is that his children and grandchildren were inspired by his example to share stories of their own.

Claire wrote, ““Dad taught us how to tie our laces, tie a knot in a tie, play chess, and teach us all his childhood jokes, trick’s and poems like Ooey Gooey and Two Dead Men Got Up to Fight – something he carried on with his grandchildren. When I left home, mum and dad would come over every Sunday for dinner. I remember when I told him I was having twins and he was to be a grandad for the first time, he was so proud.”

Kerr said, “I remember spending time with my Grandad and playing the Xbox for like 5 hours trying to help him complete the Perfect Dark game. Just sitting and talking and drinking and playing games is one of my favourite memories of him.”

Kelly told us a big secret; the time she made Wullie fall down Blackford hill. As she wrote, “What only him and I knew was that it was me that caused him to fall! As I got older, anytime it was brought up I knew that if I looked at grandad, he would give me a subtle wink and tell people the usual story “Aye I was slipping down the hill and caught a daisy which saved me!”

Mark & Liam remembered “being dropped off at school in his god-awful Polo sedan that we couldn’t bear to be seen in. Ironically that was the car we learned to drive in too… He introduced us to games consoles, and let us watch 18+ movies when we stayed over – probably because he didn’t want to watch our crap. We remember helping him with modern technology, only for him to say, “that’s why I have grandchildren.”

Erin remembers “laughing at all his jokes, chatting to him about crime novels, making him omelettes and pouring his rum because I gave him big measures,” and Ariane said, “I remember happy times in the garden with grandad hunting snails and tending to the flowers and veg.”

In the sixteen years that I’ve been a celebrant, funerals have definitely changed, and what more and more people want to hear now are stories about the person they loved so they can say, “yes – that really is what my dad – or my friend, or my colleague – was like”. In all that time, I’ve depended on the memories of the living for those stories on all but a handful of occasions. All I hope is that in the years to come, more people are inspired by Wullie’s example, and take the time to tell their story in their own words.

I got a lovely email from Claire this morning, which is what prompted me to write this post. As she said, “The family would like to thank you for our dad’s tribute on Saturday. You brought his story to life and many said they could hear his voice through you which was a great comfort.”

It’s a great comfort to me to know that. We celebrants usually see ourselves as speaking on behalf of the family, but it was a real privilege to have spoken on behalf of the remarkable William McGinnis himself.

0 Comments Leave a comment